[ad_1]

MUMBAI: State-owned banks will jointly move the government to regain their power to stop dodgy borrowers from fleeing the country.

Last week, several high-street banks took a decision to make a joint representation to the finance ministry for obtaining a statutory backing to their ability to issue ‘look-out circulars‘ (LOCs) that alert immigration authorities and restrain errant, unresponsive borrowers from crossing the borders and escaping the local law enforcement agencies.

“It is a tool we don’t want to lose,” a senior industry official told ET, confirming the decision. “We have reasons to believe that it helps in loan recovery,” said the person.

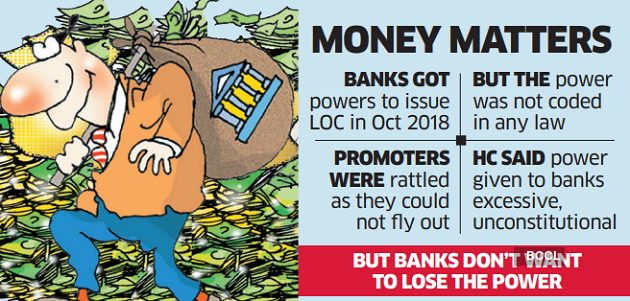

Banks primarily issued LOCs to fraudulent borrowers and wilful defaulters – who they suspected could run off to take the residency or even citizenship of another country. However, last month, the Bombay High Court struck down the powers of chairmen, managing directors and CEOs of all public sector banks to issue LOCs on the grounds that the ‘right to travel abroad’ cannot be taken away by an executive action and the powers given to bank chiefs is arbitrary and unreasonable.

The ruling did not go down well with bankers who are keen to retain leverage over such borrowers. How would New Delhi, which may well share the views of banks, go about addressing this?

According to Chirag Naik, associate partner at the law firm MZM Legal LLP, “In view of the court ruling, either a new law has to be enacted, or an existing law will have to be amended to make the statutory basis and procedure for issuance of an LOC and introduce within it a detailed procedure where these requests are adjudicated and processed by an independent Tribunal/Authority.” “The government,” said Naik, “may also choose to adopt a system inspired by blocking and tapping procedures under the Information Technology and Indian Telegraph Act.”

Bank heads were allowed to issue LOCs in a home ministry circular in October 2018 – months after the Nirav Modi-Mehul Choksi scam came to light. It was spurred by requests from the finance ministry and the department of financial services.

Public sector bank CEOs were thus added to a list of officials who could request for opening LOCs. The latter included officers not below the rank of deputy secretary (GOI), joint secretary (state government), district magistrate, superintendent of police (SP), SP in Central Bureau of Investigation, zonal director in Narcotics Control Bureau, deputy commissioners of apex tax bodies, assistant director of the Enforcement Directorate among others.

The new power given to banks was criticised by some of the industry associations when some of the big names in Corporate India were rattled to discover (only after reaching the airport) that they were barred from flying out. Some felt that the enforcement agencies pushed for extension of LOCs (beyond a year) even though they had very little ground.

In the case of banks, the court had said that since a bank has financial interest in recovery of loans, it cannot be the judge and executioner at once. However, the court has left the room open as it also said that “..this judgment cannot and will not prevent the Union of India from framing an appropriate law and establishing a procedure consistent with Article 21 of the Constitution of India.”

The issuance of LOCs is governed by a home ministry letter dated September 5, 1979. The directive was subsequently fine-tuned to lay down the seniority of officials who could issue LOCs and under what conditions. Bank chiefs were empowered (through an ‘office memorandum’) after non-performing assets (NPAs) had peaked in loan books of financial institutions, and a few high-profile borrowers had left the country.

[ad_2]

Source link